Building offline-ready apps: the scale of offline functionality

It’s surprising how many apps simply bail out if you’re not online. Make a quick test: grab your phone, turn off the network and open random apps. See how many of them even show you something, beyond an error message.

If we start talking about Web apps, the percentage of them that works offline quickly goes to zero.

Even though most apps could cache data and provide quite a lot of offline functionality, teams often don’t take the time to think through how their software may behave without a server to talk to.

True, the list of challenges can be daunting. Here are some of the difficulties I’ve had the pleasure of running into:

- Setting up caching strategies

- Avoiding data duplication across caches

- Setting up local mutations and optimistic updates

- Avoid accepting local mutations that end up being rejected by the server

- Syncing server data with local data

- Adapting existing solutions to your own infrastructure (good luck persisting to a relational database)

- Evolving your schema, while ensuring you don’t break apps with older data stored locally

And some web specific ones:

- Avoiding or removing broken service workers

- Dealing with IndexedDB, its API and its terrible performance

- Combining cached server-side rendered pages with local data

- Managing storage quotas to avoid your app’s data being wiped

Which capabilities do you need?

Recently, I’ve been building (sidenote: A “topo” is a guide book for an outdoor climbing spot. ) an outdoor climbing app. It’s intended to be used even in remote places, with no guarantee of Internet access. It also allows offline work for the cartographers (WIP).

One thing I’ve realised while working on Topogether’s offline mode is that it’s incredibly helpful to know upfront exactly what capability you need.

However it’s an evaluation that requires a clear mental model for thinking about offline readiness. I wish there were more resources to help developers get started on that front, so here is my way of thinking about it.

My current mental model is that each app wants to fit somewhere on a scale of offline functionality, where each step builds on the previous one by adding new capabilities and implementation gets progressively harder.

Once you know where you stand, I find it becomes actually quite easy to evaluate solutions and you end up building much faster.

Prelude: designing offline UIs

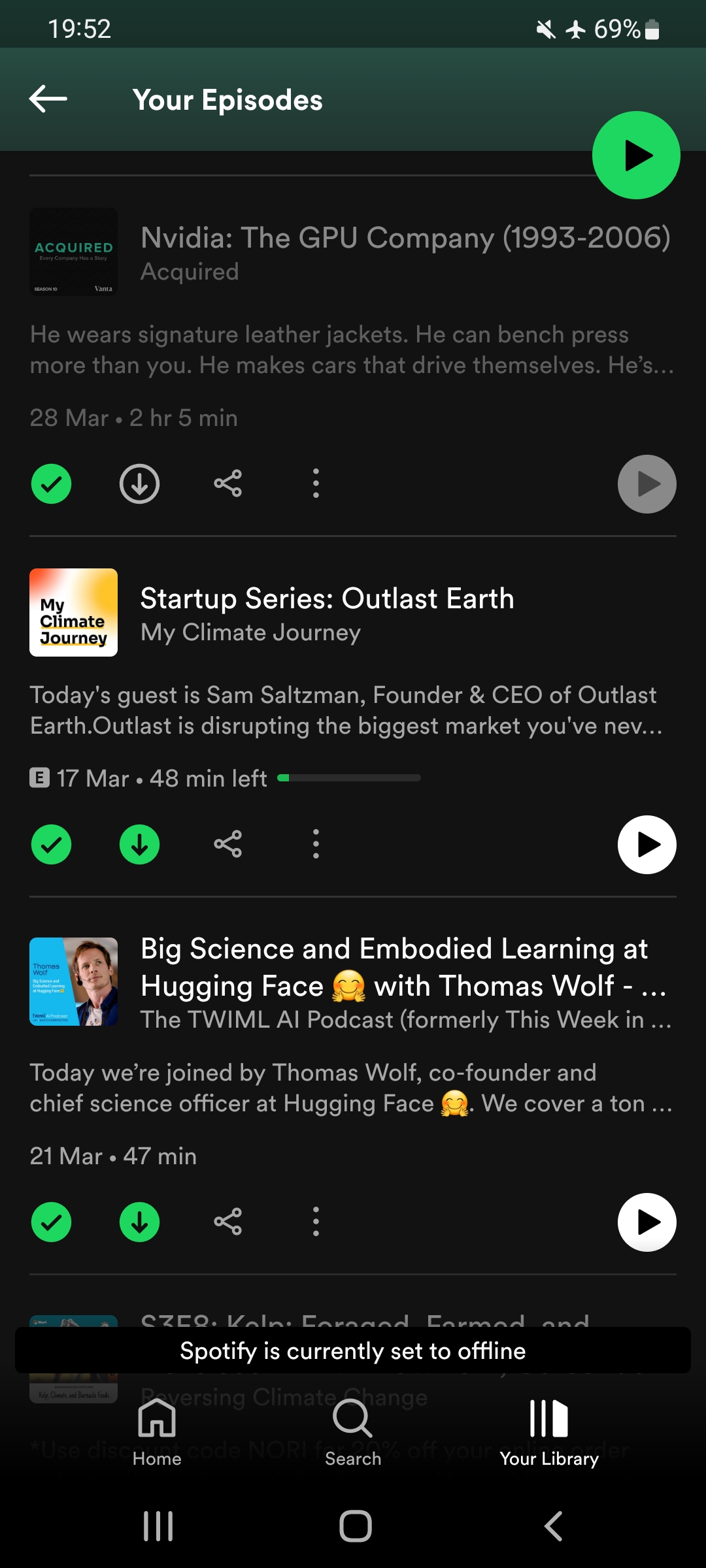

Before diving into any specific level of offline functionality, there is an UX pattern that is common to all cases below: the interface should recognize when the application is offline and clearly tell the users which actions are possible, and which are not.

Anything else will be confusing to the users and may cause them to end up stuck on an endless spinner, when they would have been happy sticking to offline actions.

Caching for offline reading

The first step to making your app work offline is to ensure that it can display content without connecting to a remote server.

At its simplest, this means showing some fallback page, explaining that the app is offline. On the web, browsers handle this for you, but that’s not the case for desktop or mobile apps.

Going further, you may want to cache some content that the users can browse while offline.

On the web, this means adding a service worker and (sidenote: Please save yourself the trouble and use Workbox. ) to cache your static assets and pages. For native apps, this means storing the data necessary to render some chosen pages in the backend of your choice.

Data fetching libraries often end up providing an interesting middle ground, where you can start using them to handle async data loading and caching for performance, then to persist the cache across sessions and provide offline reading, before finally moving to the next tier and allowing offline mutations. Libraries like React Query or GraphQl clients like Apollo, Relay or urql all fit into that category.

Update queuing and optimistic UI

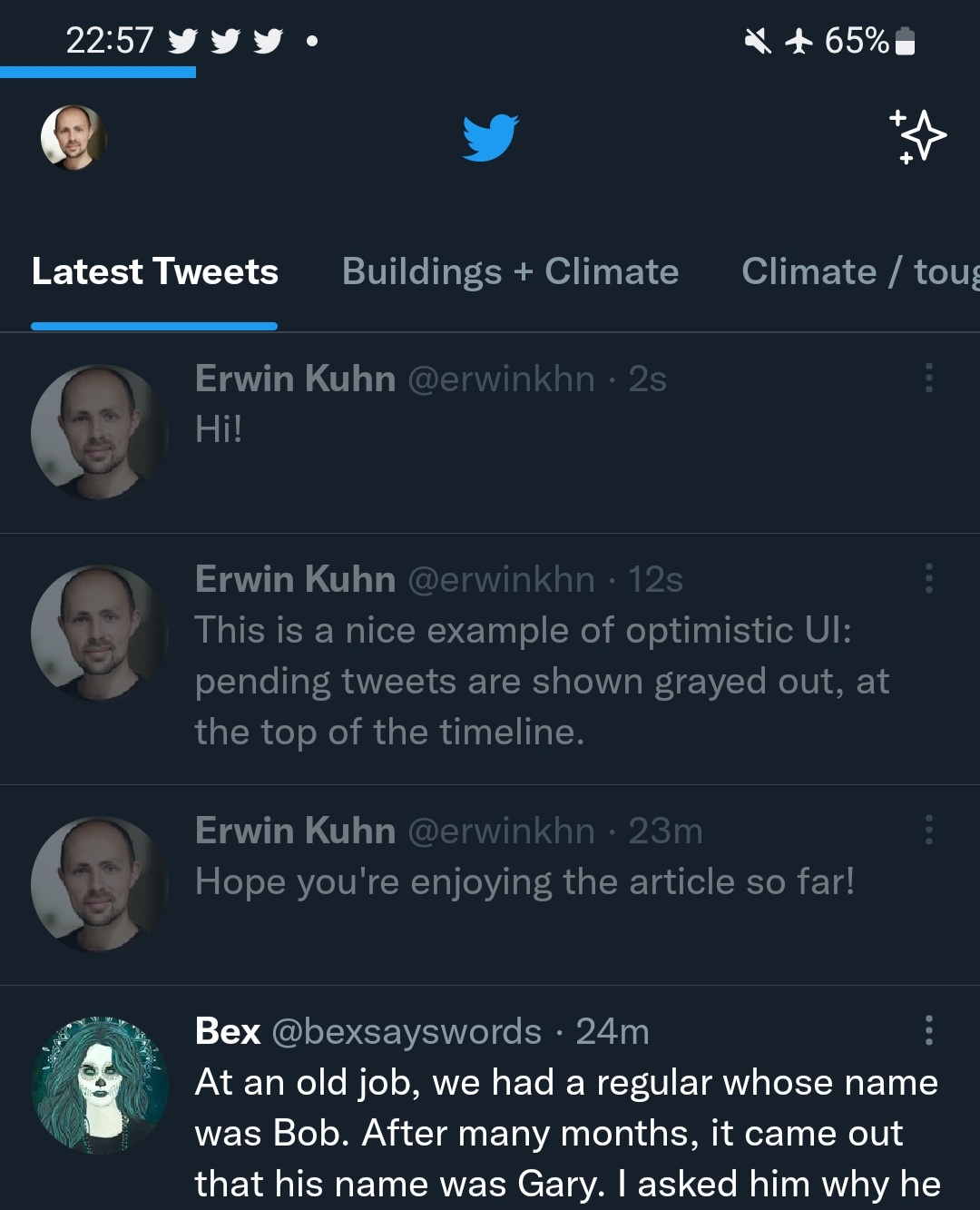

The next step is probably the one relevant to most applications: if you want to provide full offline functionality, it’s highly likely that your users may want to interact with the application in some way. For example, liking an article or submitting a tweet.

In this case, the simplest approach is to do two things: queue and persist offline updates, to send them to the server once the app is back online, and reflect optimistic updates in the UI, to let the user see the updates that have been applied, but not sent to the server yet.

You’ll have to be careful regarding retries, error handling and displaying UI for the updates based on their status (pending, successful, rejected).

If your updates require the user to be authenticated to be accepted by the server, you’ll also have to think about what happens if the user comes back online with queued updates, but their session expired. You don’t want their updates to be lost because they are rejected by the server, while they are trying to log back in.

Let’s take a concrete example: a user has updates A, B and C queued and comes back online. All three are sent to the server, but only B actually goes through due to bad connectivity at that time. Here, B is considered successful and either the response provides the new data from the server, or the app can manually refetch it, to make sure the data associated with B is up-to-date.

Status: B accepted; A, C pending.

To avoid discarding updates too easily, you may have a policy of retrying on network errors and retrying at least twice before considering that an update is being rejected by the server. The app sends A and C again and receives an OK response for A, along with fresh data, and an Unauthorized for C.

Status: A, B accepted; C pending.

The app sends C one last time and it is rejected as Unauthorized again. At this point, it considers that the update is being rejected by the server (maybe something changed while the user was offline). C is marked as definitely rejected and the user should be notified accordingly.

Status: A, B accepted; C rejected.

Due to how easy it is to make a mistake in this process, I’d highly recommend adopting a systematic approach.

Tools for the job include:

- General query clients, like React Query

- GraphQL clients: Apollo, Relay or urql

- Redux offline, which splits the lifecycle of a queued update into an effect (the network request), a commit (if successful) and a rollback (if rejected)

Going local-first: client-side databases

Highly interactive apps, like any kind of graphical or text editor, will need to go beyond caching & update queuing. Contrary to an application like Twitter, offline updates are not considered as “pending” and displayed differently within the UI, but directly merged into the underlying data. When 300 offline updates happen to the same piece of data, only the latest version is sent, instead of replaying every operation on the server.

For this purpose, what you want is a client-side database, that acts as the source of truth for your application and is synced in the background to the main database. In this local-first model, the remote database ensures persistence of data, provides fresh data to the client-side database and performs conflict resolution, if necessary.

The desired properties of a client-side database are the following (IMO):

- Queryable and persistent are prerequisites for the job.

- Syncable, ideally with enough flexibility to use any backend you want.

- Reactive: it provides hooks to automatically update the UI when something changes in the DB.

- Partial: the client-side database does not need to be a replica of the whole remote database to be able to sync with it.

- Lazy: the database does not need to load everything into memory on initialization.

- Schema-aware: changing the shape of data suddenly becomes much harder when that data is split between a remote database and an unknown number of client-side databases. Having a tool that knows your schema and allows specifying migration strategies that can be deployed to your users will save your life and their data.

Let’s do a quick rundown of some client-side databases.

CouchDB / PouchDB

CouchDB is a widely-used document store designed for syncing replicas. PouchDB is a compatible JavaScript implementation that provides a browser / React Native client and Node.js server.

Pros: mature and proven in production, simple API, file attachments, lots of plugins.

Cons: can’t bring your own infrastructure, no per-document access control (access control = splitting into different databases, which prevents querying across all of them), no built-in reactivity.

RxDB

RxDB is a NoSQL JavaScript database, which was initially built on top of PouchDB, but now supports other backends.

Pros: reactivity, schemas & migrations, multi-tab sync, realtime features, built-in CouchDB/PouchDB, GraphQL or customisable backends, incrementally updated queries, experimental web worker offloading.

Cons: 100kB minified + gzipped, but that’s probably fine for the type of apps that need its features.

WatermelonDB

WatermelonDB is a relational database, which is quite rare to find client-side. It was mainly built for React Native, to leverage SQLite and its speed, but also supports IndexedDB on the web now.

Pros: reactivity, schemas & migrations, lightweight (36kB minified + gzipped), customisable sync, leverages SQLite for speed & only loading data on demand (React Native only).

Cons: requires both a schema for the database and models for each entity (this is very flexible, but also very repetitive), only table creation / column creation are supported for migrations, advanced docs are still incomplete.

More resources

For a deeper dive into client-side databases, I highly recommend Jared Forsyth’s In Search of a Local-First Database, as well as the Opinions section of RxDB’s documentation. The author also has a benchmark for client-side databases in the browser.

Offline & collaborative apps

OK, we’re now entering experimental territory. Here, we are talking about apps where users can collaborate in real-time, drop into offline mode & continue working, before coming back online and seeing their changes merged with other work that happened in the meantime.

Upfront warning: any solution in this area should be considered experimental technology, will likely have major limitations and will require a lot of tweaking.

Still interested? Good! It’s significantly easier to build offline collaborative apps than it was even 5 years ago. By significantly easier, I mean that it’s now possible for individuals or small teams, and not just organisations with a lot of engineering power.

The key to tackling this problem is conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs). They are data structures that look like regular objects, arrays, sets or maps, but are able to synchronise any two replicas together.

The guarantee they offer is strong eventual consistency: any two replicas that have seen the same changes end up in the same state.

Synchronisation can happen in real time or after an extended period of time, making them perfectly suited for offline collaborative apps. Synchronisation can also happen between any two peers, without requiring a server for conflict resolution.

In that model, a server is mostly helpful for persistence, propagating messages to peers and querying over all of the existing data (which will likely be split across multiple CRDT documents).

To learn more about how CRDTs work, I highly recommend James Long’s talk CRDTs for Mortals, Lars Hupel’s series on their mathematical foundations, or any of the resources on https://crdt.tech/

The two main implementations today are Automerge and Yjs. In their current state, Yjs is lighter (24kB), faster and seems to have more integrations (like IndexedDB, Websocket or WebRTC backends). Automerge has a more flexible API and the ability to expose conflicts, when two users have concurrently modified the same value in a map or an object.

While both support full JSON models & text editing, (sidenote: I have also written more extensively about the limitations of current CRDT implementations (& how they could be addressed). )

- document size only grows with time: deleted items are just marked, not removed

- only tree-shaped data: no graphs, you’ll have to normalise yourself

- no move or splice operation within arrays or text (these are really hard problems)

- no schema awareness, so you’re on your own for managing decentralised data migrations (although Cambria is promising research on that subject)

- no authorization, all peers with access to a CRDT can send any operation

- syncing to most databases is hard, you’ll have to write a custom server + adapter

Whether such limitations are deal breakers is up to you and your use case. There are apps in production running on both Automerge and Yjs, so joining that club is definitely possible.

Appendix: Handling sensitive information

If you’re storing sensitive information, like banking or medical data, on the user’s device, it would be wise to adopt some security measures.

For instance, instead of keeping the user logged in until they are back online, you may add an authentication layer on app restart. This can be a stored password / PIN code or a (sidenote: Also available through the Web Authentication APIs! )

In that case, the user’s local data should be encrypted while at rest and only decrypted using a secret coming from the authentication layer.

The unfortunate part is that I haven’t seen any good library to do this, so you likely will have to implement your own solution, both the authentication layer & the encryption as a wrapper around your storage method.